Web design © Graeme de Lande Long. Terms & Conditions.

Community Website

Scaynes Hill Village

Like it or not fracking is a local, national and global issue that we cannot ignore. Recent national news has included the anti-fracking demonstrations at Balcombe, the Labour Party pledge on freezing energy prices and the latest sobering UN Climate Change Report confirming the influence of human activity on climate change. These items are not unrelated.

The ‘Fracking’ debate - to frack or not?

05 October Posted by Graeme de Lande Long

Fracking is short for hydraulic fracturing of rocks (Ref 1), the method used in non-conventional extraction of gas (and oil) from shale rocks that lie at depth in many parts of the world including Britain. Despite some formidable opposition to this new technology, including bans or moratoriums on fracking in other countries (eg France, Germany, Bulgaria & Tunisia), our Government has come out in favour of it as providing a cheap source of home grown energy (Ref 2). Consequently huge tax breaks are being offered to producers of shale gas and oil as well as financial incentives for communities based near potential fracking sites.

I first became aware of the fracking debate about a year ago when I was told that planning permission had been granted for exploration of oil at Balcombe. Previous exploration there in 1986 had identified oil but with the technology then available it did not look to be commercially viable. However, with the development of fracking the exploration company Cuadrilla, who already had the licence for exploration and development in that area, was starting to show an interest.

Initially I decided to try and keep an open mind. Being a water engineer with more than a passing knowledge of related subjects such as groundwater, drilling, deep mining subsidence and seismicity, as well as having a keen interest in sustainability, I decided I should find out as much as I could in order to see whether I should support fracking.

- Release of shale gas or oil by means of fracking will provide a plentiful source of home grown energy that will lower energy prices and provide much needed jobs (Ref 2).

- As North Sea gas output continues to decline, shale gas produced in the UK will provide improved energy security by reducing reliance on imported sources.

- In order to meet the Government's legally binding targets on reducing greenhouse gas emissions a large number of coal fired power stations will be de-commissioned over the next two decades (Ref 6). Replacing coal fired stations with gas fired ones which emit less greenhouse gases will help meet the targets, so the addition of shale gas will be helpful.

- Development of onshore unconventional gas resources by fracking will not damage the environment as has been reported elsewhere (eg USA). Britain has one of the most stringent regulatory systems in the world to protect the environment and shale gas exploitation will create only very minor changes to the landscape (Ref 4).

Summary of findings

Economics - the case for lower energy prices and significant job creation has not been adequately justified (Ref 3, Ref 11) and it is likely that for the same level of investment in renewable energy technologies more jobs could be created in the UK (Ref 10).

Energy Security - the parliamentary cross party committee on Energy and Climate Change concluded that the effect on energy security would not be large and that energy security considerations should not be the main driver of policy on the exploitation of shale gas (Ref 15). Development of our own domestic renewable and low carbon energy sources could provide the same level of security (Ref 7).

Global greenhouse gas emissions - replacing dirty coal fired power stations with gas fired ones would help reduce greenhouse emissions. However, the gas fuel could equally well come from imported gas as from domestic shale gas (Ref 6). To meet the targets we would still need a very significant amount of renewable energy sources (eg wind, wave, biomass etc) as well as other low carbon sources (eg nuclear). Investment in and promotion of shale gas is likely to divert the necessary investments from renewable technologies, and so would be counter-productive (Ref 15).

Local environmental issues - the potential for environmental damage from shale gas/oil is high (Ref 8); with strict regulatory control the probability of groundwater contamination is potentially low but the impact if it happened could be very severe, while dependence on a strict regulatory framework appears unrealistic. The industrialisation of the countryside with numerous closely spaced drilling sites and the infrastructure to service them would have a significant impact on our landscape.

<< Back to News

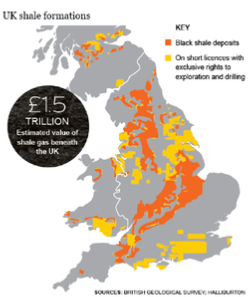

Where is fracking likely to happen?

Licences for oil and gas exploration have already been sold by the Government to interested developers such as Cuadrilla and IGas covering large areas of the country where the geology is favourable. Fracking has already been started by Cuadrilla in NE England and great interest is now being shown in Yorkshire. The Weald, covering Sussex and parts of Surrey, Kent and Hampshire, is geologically suitable and the entire area from Alton and Petersfield in the West to Tonbridge and Hailsham in the East is already licensed to various developers, who are beginning to demonstrate their interest.

Overall conclusion - Neither the economic argument for shale gas nor the case for it helping to meet the targets on greenhouse gas emissions hold water, and the security issue would be equally well addressed by developing our own sources of domestic renewable energy. The price of the likely environmental impact involved in extracting shale gas/oil does not seem worth paying in pursuit of yet another source of carbon based fuel that ultimately does not help us achieve our global commitments on greenhouse gas emissions.

Fracking landscape in US

Balcombe is one of the first sites in the Weald area to have reached the stage of being granted Planning permission, which has allowed Cuadrilla to carry out exploratory drilling, but as yet no fracking. Other sites where Planning permission has been granted are near Lingfield, Cowden and Billingshurst with other applications being considered near Fernhurst and Wisborough Green. Gas has already been identified at Bolney, which is in the same area licensed to Cuadrilla, as are Lindfield and Scaynes Hill.

Government case for extracting shale gas or oil

The Government's case for pursuing the development of shale gas or oil is principally based on:-

Put succinctly the above indicates there are broadly four principal topic areas for consideration; economics, energy security, global greenhouse gas emissions and local environmental issues.

For those of you who just want the short answer I give a summary of the conclusions I reached below. For those who would like to know how I came to these conclusions I have given some more detailed discussion, and for those who really want to check out my sources and do their own research I give the full list of references (with hyperlinks) at the end (the underlined (Ref X) in the text also act as hyperlinks).

Further information

Once a developer has obtained an exploration licence from the Government the next stage is to negotiate with the landowner the right to access the land as well as obtain planning permission for the right to use the land from the local Minerals Planning Authority, which for this area is West Sussex county Council (WSCC).

In 2010 when Cuadrilla submitted their planning application for drilling at Balcombe there was little interest or knowledge of fracking and it was approved by WSCC with little fuss. However, as a result of recent events WSCC would now consider any further applications with more openness and consultation. Cuadrilla has had to leave the site in Balcombe since their Planning Consent lapsed at the end of September, but they had not finished drilling and had done little testing. It looks to be their intention to submit a new application in the New Year.

Since exploration licenses have already been granted over much of the Weald control in relation to exploratory drilling, and ultimately fracking, now rests with WSCC. If you have views about whether you think WSCC should or should not be granting planning permission for shale gas/oil developers I would encourage you to make your views known to our local councillor for Lindfield & High Weald, Mrs Christine Field, either by e-mail (christine.field@westsussex.gov.uk) or by speaking to her in person (01342-810310).

Detailed discussion by topic

Economics

The Government foresees fracking as lowering energy prices largely based on the experience in the US where the fracking revolution has resulted in much lower gas prices. However, Lord Stern, author of the widely respected Stern Report on the financial implications of climate change, has described this as baseless economics (Ref 3), pointing out that there is a huge difference between the US and European gas markets. Although gas is an internationally traded commodity the US has essentially been an isolated market, which has meant that increases in supply have pushed down prices because gas producers have had limited scope to export to a higher bidder. By contrast, the UK is part of an integrated European market through a series of giant gas interconnectors, meaning that even a huge increase in domestic gas production would be unlikely to dent the prevailing price for the continent.

Other factors such as less promising geology and higher population density in the UK mean that shale gas development is likely to be more expensive than in the US. Furthermore the International Energy Agency has forecast natural gas prices are likely to rise by 40% by 2020, even with an influx of cheap shale gas (Ref 6).

The Government's claim that shale gas exploitation would give rise to 70,000 new jobs in the UK needs to be treated with caution as, according to US experience, numbers can be over-stated (Ref 9); most employment is during the drilling phase, which only lasts around a year and many jobs go to transient specialist workers who move from one well to another. In Pennsylvania for example 70% of gas well drilling jobs went to people from out of state.

In contrast other research from the US shows that investing in renewable energy creates more than two to three times as many jobs as investing the same amount in gas (Ref 10). In the UK nearly 21,000 new jobs were created in the renewable sector in the year 2011-12 (Ref 11) and it is estimated that the renewable sector could support 400,000 jobs by 2020 (Ref 12).

Energy security

With the decline of North Sea gas production the UK is now a net importer of gas, so this is one area where domestic shale gas might be seen to be beneficial. However, the viable reserves in the UK may not be as large as some predict (Ref 5) and the time required to develop them may be longer than has been the case in the US due to a much greater population density in the UK and our Planning system, so much reliance should not be placed on shale gas. Furthermore the gas we import is mainly by pipeline from places like Norway and the Netherlands, countries with a strong record of supplying gas to the UK (Ref 15), although a small part (10%) is imported in the form of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) from Qatar.

The Government's own cross party committee on Energy and Climate Change in their report of session 2010-12 on shale gas (Ref 15) reviewed the issue of its contribution to energy security and concluded that "Shale gas has the potential to diversify and secure European energy supplies. Domestic prospects-onshore and potentially offshore-could reduce the UK's dependence on imports, but the effect on energy security is unlikely to be enormous. We conclude that energy security considerations should not be the main driver of policy on the exploitation of shale gas."

Greenhouse gas emissions

The Energy Bill 2012-13 is a blueprint for power generation in the UK over the next few decades while meeting legally binding targets set by the 2008 Climate Change Act (reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 50% in 2025 and 80% in 2050 based on 1990 levels). To achieve these targets a further target has been set to have 30% electricity generation by renewable sources by 2020, principally to replace dirty coal fired stations, which are to be phased out. The relative carbon footprints of different power generation methods is well explained by the Parliamentary Office of Science & Technology (Ref 14). To meet its targets, the government needs to increase the amount of energy produced by wind and nuclear power, in particular, but also by other forms of clean energy such as biomass (Ref 6).

However, government is also aware that without sufficient investment by energy firms in the private sector the necessary amount of renewable power may not be implemented quickly enough to bridge the gap. If development/implementation of sufficient renewable sources of energy takes too long then to meet the shortfall and stop the lights going out, as well as meeting the emissions targets, the government will have to resort to short-term measures, such as building new gas plants (possibly using shale gas), that can be built relatively quickly, or simply importing more energy from overseas (Ref 6). Shale gas from fracking would therefore seem to be a potentially attractive Plan B.

However, the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) and other respected organisations, such as Chatham House and the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, are all on record as admitting that investment in the production of shale gas would probably reduce the incentive in the low carbon alternatives required to meet longer term emissions goals (Ref 15), a danger that has also been highlighted by Friends of the Earth (Ref 8).

Like conventional natural gas, shale gas is basically methane, a greenhouse gas itself, which has a greenhouse effect many times that of CO2. In all gas production a small amount of gas (fugitive gas) escapes/leaks into the atmosphere, but shale gas production creates comparatively more fugitive gas and due to greater energy and water use for its production its carbon footprint is greater than conventionally extracted offshore gas. The effect of fugitive gas is hotly disputed, being considered small by some but by others to make shale gas nearly as bad as coal. Therefore, although shale gas from fracking might seem a potentially attractive option it may not be an effective option if emissions targets are to be achieved.

Environmental issues

The principal environmental objections that have been raised (Ref 8) are:-

- Potential contamination of groundwater by fracking fluids

- Use of large amounts of water, a significant proportion of which has to be treated as contaminated waste

- Significant vehicle movements required to bring fracking chemicals/water onto sites and remove contaminated wastewater from sites.

- The large number of sites at relatively small intervals required

- Potential to cause minor earth tremors during fracking

- Impact on flora and fauna and visual impact on the landscape

- Air pollution, noise and dust

Such environmental risks were recently reviewed in a report for the European Commission, which assessed the cumulative impact of fracking at several sites as having a high risk of causing local environmental problems including groundwater contamination, surface water contamination, water resource use and air pollution. The above impacts are all important considerations but I discuss only some in more detail. The basic method and principles of fracking are described in a Friends of the Earth Briefing note (Ref 8), which also clearly summarises the environmental risks.

Fracking is a water intensive activity. At the one site fracked in the UK Cuadrilla used nearly 9 million litres, while in the US this is a minimum with amounts up to nearly 30 million litres being reported. If there are six wells per drilling pad (a typical number) and each well is fracked twice, then the total volume of water per site would be about 250 million litres. The volume of water required might not be significant at national level but there could be local and regional problems. For example, the Cuadrilla drilling near Blackpool is within the River Wyre catchment - the Environment Agency identifies that all zones in the catchment are classified as either 'over licenced', 'over abstracted' or 'no water available'. These problems could be worse in areas proposed for fracking that have suffered from drought, such as South East England, and could be further worsened by climate change.

On average about half of the fracking fluids (water/sand/chemicals) get recovered and are only partially recycled which means that the other half stays in the ground to go wherever the geology allows. What is not recycled has to be removed from site as contaminated waste and disposed of appropriately. Some of the chemicals used, eg polyacrylamide, are considered potentially carcinogenic. Generally fracking takes place at depths well below useable groundwater aquifers so this may not be too concerning although there are fears that the fissures created by the fracking may extend upwards to groundwater sources. As the underground geology cannot be known in minute detail there can be no guarantee that this does not happen, although it may be unlikely.

Of more concern is the integrity of the lining to the well, where it goes through layers containing groundwater aquifers. The lining or steel casing, which is cemented in place, should normally prevent contamination of the groundwater but is obviously a vulnerable element and so there is a risk of groundwater pollution from improperly constructed wells, which is what has occurred in some shale wells in the US. DECC has stated that while there might have been cases of well integrity failure on some US shale wells, they "do not believe that such a situation would occur in the UK" and,despite the advice from the cross party select committee on Energy & Climate Change that the HSE should test the integrity of wells before allowing the licensing of drilling activity (Ref 15), they have left the responsibility of ensuring that the well design is "safe and fit for purpose" with the operator (Ref 16), saying that the operator's obligation would be "checked very carefully by the Health and Safety Executive".

However, it was revealed on BBC's Newsnight in 2012 that the Health and Safety Executive neglected to perform independent analysis of Cuadrilla's Preece Hall well in Lancs before fracking started there. Instead they relied on the company's own reports (Ref 13).

The shale gas industry says that chemicals are a very small percentage of the liquid pumped underground, but given the enormous quantities of water used (see above), this still represents a huge quantity of chemicals. Typically the chemicals may be about 0.5% of the water used; this means that each multi-well drilling pad would use 1 million litres of chemicals, equivalent to about a third of an Olympic swimming pool.

In its published Policy Statement on Fracking in the UK (Ref 17) the Chartered Institution of Water & Environmental Management (CIWEM), an independent professional body well respected in the water industry, states that "the UK should proceed cautiously, adopting the precautionary principle and not encourage fracking as a part of our energy mix until there is more evidence that operations can be delivered safely, that environmental impacts are acceptable and that monitoring, reporting and mitigation requirements are comprehensive and effective."

Shale gas can only be extracted from the area where horizontal drilling and subsequent fracking are possible, and there is a limit to the distance over which horizontal drilling can be achieved. This depends on many factors, but the maximum distance for a horizontal drill would be 2 miles and it would generally be less. It is therefore necessary to have fracking well sites at frequent, say I mile intervals or less in all directions across the landscape in order to extract the gas from a shale formation. With all the infrastructure needed to bring to site the large volumes of water, equipment etc. and to remove the waste products there is likely to be a significant industrialisation of our landscape as well as a large increase in local vehicle movements.

References

Note: There is a massive amount of material published about this subject - just Google "fracking" or "shale gas" and you will see what I mean. I have used the numbered references below in compiling this article in an attempt to provide a balanced selection of material that has tried to avoid some of the more extreme or sensationalist material. However, if you want to do your own research I give some pointers after the number references below.

1. What is fracking and why is it controversial? BBC News (27-Jun-13)

2. Fracking ban would be a big mistake says Cameron. The Guardian (8-Aug-13)

3. Baseless Economics The Independent (3-Sep-13)

4. You must accept fracking..says Cameron The Telegraph (11-Aug-13)

5. Fracking in the UK: half a century of gas supply? Full Fact (12-Aug-13)

6. Energy Bill Q&A BBC News (29-Nov-12)

7. Why it's time to take our foot off the gas Friends of the Earth (May 2012)

8. Fracking briefing note Friends of the Earth (May 2013)

9. The great debate over shale gas employment figures Industry Week (11-Aug-11)

10. The economic benefits of investing in clean energy Political Economy Research Institute (June 2009)

11. Renewables Investment and Jobs. Department of Energy & Climate Change (20-Sep-12)

12. Renewable Energy: Made in Britain Renewable Energy Association (2012)

13. Newsnight on Fracking (20-Mar-12)

14. Carbon Footprint of Electricity Generation Parliamentary Office of Science & Technology (Jun-11)

15. House of Commons Energy & Climate Change Committee 2010-12 (10-May-11)

16. Government response to Parliametary Committee

17. Hydraulic Fracturing of Shale in the UK Chartered Institution of Water & Environmental Management (Oct-2012)

Further Research

The pro-fracking case is being made by the Government Department for Energy & Climate Change so it is principally their publications and what is released to the press that puts the pro-fracking case. Visit the DECC website and to find relevant information put into the Search box at the top of the page either "fracking" or "shale gas". Refs 14, 15 & 16 above are also worthwhile reading.

There are a number of anti-fracking campaigns and websites that can give you links to further information. A few relevant ones are:-

- Frack Free Sussex

- No Fracking in Balcombe Society (FiBS)

- Friends of the Earth and Ref 8 above gives a comprehensive summary of the issues

<< Back to News